For the last several years, I’ve attended many game design workshops and playtest events at a variety of conventions from Gencon to Kublacon. In them I have taken notes diligently (like any proper engineer and/or Capricorn would). In hopes of finding some sage advice for new-to-the-industry designers, considerable time was spent frittering over and re-re-rereading those notes. Of the recommendations collated, I have found the following three pieces of advice the most useful. While my own approach to game design no doubt shaped this compilation, nevertheless, I believe that they apply equally well to other designers. Please add more, if you’ve got a hard and fast rule to which you adhere.

If It Doesn’t Work, Rip It Out.

Really. As hard as it is to do, if some element of game play is not working, try removing the problem mechanic (and its associated pretty-bits). Even better, make a list of all of the major mechanics and rules in your game. Then ask yourself if they all have to be there. Will the game fail without them? If not, then pull them out. Once you’ve settled on the major mechanics and rules, try it again with their subcomponents. The game will be smoother for your brutality.

Also, apply the ‘Rule of Three’ to your logic: People remember best in threes. A turn should not have more than three steps. A card should not have more than three pieces of gameplay-dependent information. The winning condition should not have more than three steps. etc… If your mechanics, rules and their subcomponents require people to remember more than three facts per item, you should simplify.

Of course every game designer makes compromises. Certainly, sometimes you can keep in a mechanic that is a bit kludgey or fudge a bit on the Rule of Threes. And, usually this is done to preserve game ‘feel’, theme or narrative. But do not do it lightly.

Simplicity is better.

Think Manufacturing.

As a matter of fact, think manufacturing and shipping. The rule of thumb is that a game should cost ~15% of the final retail price per game to manufacture, provided you are doing a big run of 2,500+ games. So, were you aiming for a $50 Kickstarter basic backer level? That means $7.50 per game for manufacturing. It’s harder to do than you think. Train yourself to mold your first visions around size, complication, and weight.

Remember that the more stuff your game has, the more expensive it will be. Ask yourself does any single piece of the game add the need for extra components? For example, do 1 or 2 cards in a deck, necessitate the use of chits where none were needed before? That is to say, make certain that a lower-level mechanic itself has not created the need for more components.

Think of it as a creative challenge, right from the start. Standard cards are manufactured in 54-card sheets, so any cards will have to be in multiples of 54. Punch-board molds are expensive to design, so if you’ve got multiple chit shapes, be sure they can be evenly spread in the same arrangement across multiple boards. A small flat-rate USPS box is 5-3/8” x 8-5/8” x 1-5/8” and costs $5.95 at the Post Office. A medium flat-rate UPSP box costs $12.65. In which size will your game board fit? Fit inside of the game box with the cards, tokens, chits, playing pieces, and directions? For some information on the subject from a manufacturer’s perspective, try Panda Game Manufacturing’s Resource page. The Game Crafter’s Game Publishing Support forum also has some great advice.

Fewer pieces means a leaner (and simpler) game for production, which means less worry for you.

Have Patience (and Show Up).

Do not force your design. You know when it is not working. You know that staring at it and forcing it upon hapless alpha-playtest friends will not fix it. Sometimes the best thing you can do is walk away from it for a while… that while may be several months. Use your free time to work on another design, playtest other games, or listen to blogs on game design. Creativity is weird that way. As Elizabeth Gilbert implies in my favorite TedTalk, the best you can do is show up, the genius will come when it comes.

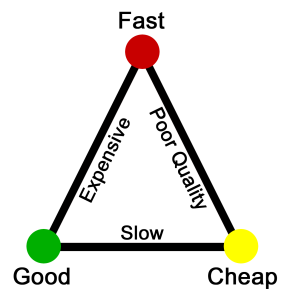

Another way to look at this is with the project management triangle. You can only ever have two of the three sides. Unless you are wealthy, your game will either be fast and cheap or good and cheap. I err on the side of good and cheap, which means fast is not possible without a quality compromise.

If you rush your design, you will not realize its potential. Patience is critical.